Introduction

When you think of air pollution or poor air quality, you probably think of scenes similar to those shown in the pictures below. And you wouldn’t be wrong for doing so.

In New Delhi, levels of particulate matter are so high that breathing here is the equivalent of smoking 50 cigarettes a day. In fact (at the time of writing), across the whole of 2021, there has not been a single 24-hour period in New Delhi where the air quality was considered to be at a ‘safe’ level for human health. Cleaning up the air in New Delhi to World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended levels could add an extra ten years to life expectancy in the city.

But it’s not just a problem in developing countries. In London, one of the most affluent cities in the world, 99% of the population is exposed to levels of air pollution that exceeds WHO guidelines. Nearly 2,000 schools in the UK are located in areas where the levels of pollutants are so high that they break the law. (

Air pollution is officially the biggest environmental factor affecting public health in the UK. The latest estimates show that poor air quality costs the UK over £20bn and that long-term exposure to man-made air pollution contributes to almost 40,000 deaths a year.

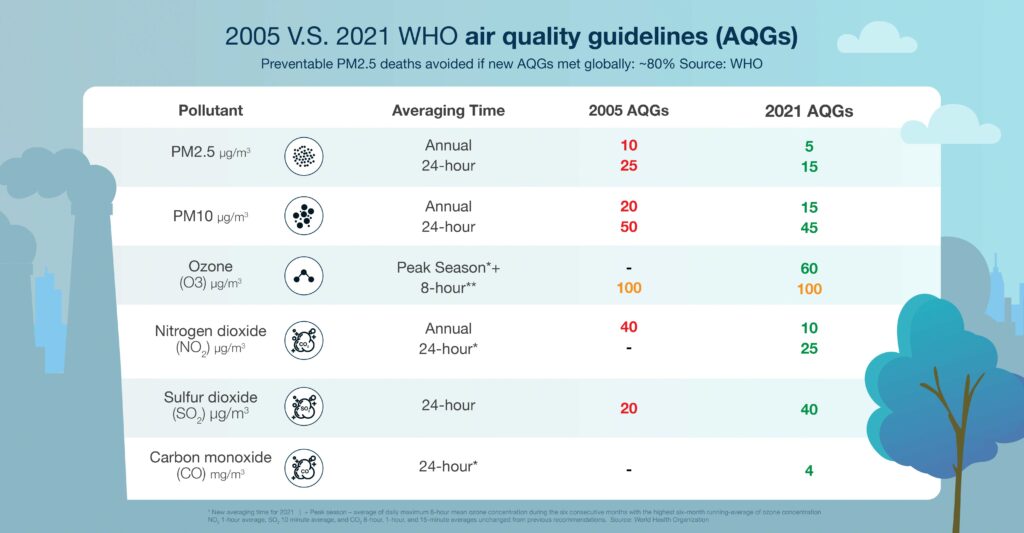

But what does ‘air pollution’ actually mean? What causes this pollution? How do we determine whether air quality is ‘good’ or ‘poor’? It’s also not just air ‘quality’ that matters – quantity is important too. Not all pollutants have the same effect on health at the same concentration. For example, benzene is carcinogenic from concentrations as low as 1 µg / m3, but ozone does not begin to have significant effects until 100 µg / m3.

What is air pollution? What’s the impact on our health?

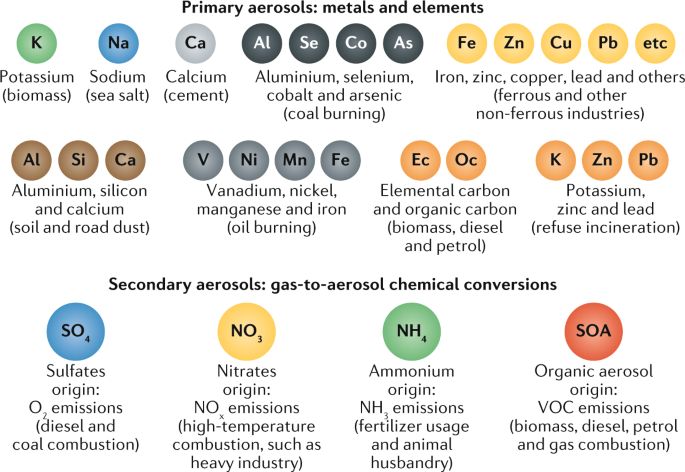

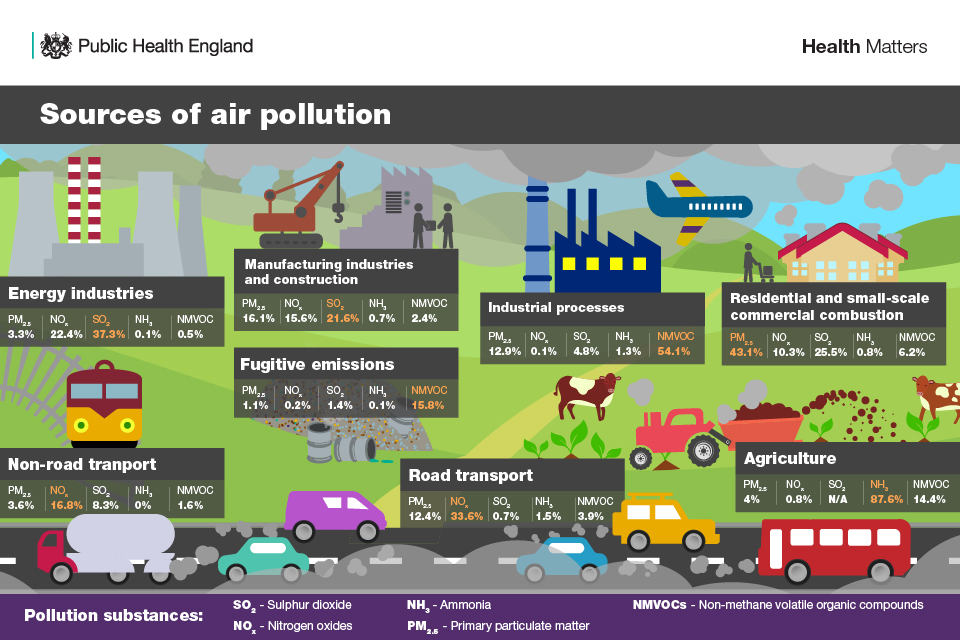

Air pollution is a complex mix of particles and gases – both natural and man-made. There are two major contributors to air pollution in urban settings – particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2).

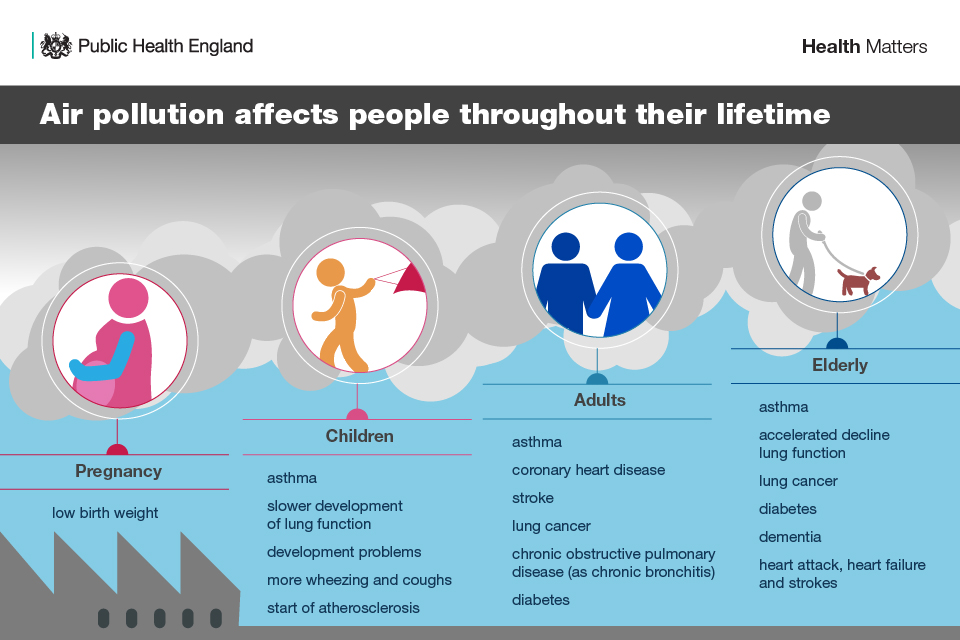

Particulate matter (PM) is a generic term used to describe the mixture of a variety of particles in both solid and liquid form, in varying sizes, shape and composition. You may often see Particulate Matter written as PM1, PM2.5 or PM10. This refers to the size of the particles in microns (µm) – particles smaller than 10µm pose the greatest risk to health as they can be drawn down in the lungs, with some particles smaller than 1µm able to pass through the lungs into the bloodstream. There is extensive research that shows long-term exposure to PM increases mortality from cardiovascular and respiratory disease.

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is a gas produced alongside nitric oxide (NO3) during combustion. Together, the two gases are referred to as oxides of nitrogen (NOx). The majority of NOx in the UK is produced by road transport. Short-term exposure to NO2, particularly at high concentrations, is a respiratory irritant that can cause inflammation of the airways leading to – for example – cough, production of mucus and shortness of breath. There is also evidence which links the presence of NO2 in outdoor air with reduced lung development, and respiratory infections in early childhood and effects on lung function in adulthood.

Other pollutants include sulphur dioxide (SO4) (produced when sulphur-rich fuels such as coal are burned), ammonia (NH3) (released by both natural and man-made sources and combines with other gases to form PM 2.5), carbon monoxide (CO) (released through the burning of fuel and is fatal at high concentrations, particularly indoors) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (a large group of chemicals that are found in many products we use to build and maintain our homes.)

‘Good’ or ‘poor’ air quality – how do we decide?

The World Health Organisation has a comprehensive set of guidelines (AQGs) which were revised in September 2021 to take into account the growing amount of evidence that poor air quality has on human health. The guidelines recommend new air quality levels to protect the health of populations, by reducing levels of key air pollutants, some of which also contribute to climate change.

Almost 80% of deaths related to PM₂.₅ could be avoided in the world if the current air pollution levels were reduced to those proposed in the updated guideline, according to a rapid scenario analysis performed by WHO. A study in 2006 found that reducing PM by 10µg/m3 would extend lifespan in the UK by 5 times more than eliminating casualties on the roads, or 3 times more than eliminating passive smoking!

What’s happening locally in St Andrews?

Fife Council have recently published an updated air quality strategy covering the 2021-2025 period. They also publish annual air quality reports and their website has useful information on the work they are doing across the Kingdom.

We are privileged to benefit from relatively good air quality in St Andrews and the surrounding area.n However, we still believe there are parts of St Andrews where the air quality could be a cause of concern. As a result, at Transition, we’re co-ordinating a team of volunteers using portable air quality monitors to track air quality at key hotspots and along routes in and around St Andrews. Hotspots include those with high levels of pedestrian or vehicle activity, such as Market Street, near local primary schools, St Andrews Bus Station and others.

For far too long, air quality monitoring has been something confined to a laboratory with such complex indices and large volumes of data that even the mathematical geniuses amongst us would struggle to get their head around. Community led action is what Transition is all about and we believe it is key the public have access to the data we gather as part of this project. We’re currently working on developing a simple public dashboard, where anyone and everyone will be able to view and explore the data we gather in a street-by-street map and understand how this aligns with the WHO recommended guidelines. (No chemistry degree needed, we promise!)

If you have any questions about our work on air quality and/or air quality and pollution in general, please email Lewis, our Sustainable Travel Officer.