Today we heard from Climate Change Commission that UK must cut land use emissions by two thirds to meet our goal of zero carbon by 2050. There has been much talk about planting trees to achieve this, but low carbon farming and taking care of our soils is expected to account for as much as 23% of those savings.

You can probably imagine what planting more trees would look like, but low carbon farming is more of a mystery. Below we give account of our visit to James Hutton Institute last week, where we talked to researchers who work on sustainable farming systems, and saw what the farming future may look like.

Dr Geoff Squire, a scientist who has conducted a large amount of fascinating research on food crops, agroecology, GM risks and much more gave us a tour of James Hutton at Dundee which includes Balruddery Farm, a testing ground for their research and the ‘living field’, and a community garden he set up to educate young pupils on food and biodiversity. We also got to meet his colleagues, Dr Pete Iannetta, Dr Ali Karley and Dr Cathy Hawes to learn more about nitrogen balance, mixed cropping, and sustainable ecology.

Living Field Garden

by Helena Simmons

Tucked behind the James Hutton Institute is the Living Field Community Garden. In a small space the team at JHI have managed to showcase lots of different habitats that can be found within the scottish agricultural landscape. The habitats include a wildflower meadow – with a spectacular wood and metal dragonfly statue; hedges and trees; soft fruit; a pond and ditch area which was a very popular hang out for the birds, and the fanciest insect hotel I have ever seen.

They have even included an impressive vegetable map of Scotland made of grass which had been planted over the summer with the appropriate crops for the area on the map. As we visited mid January, the crops have finished/been removed, but the map remains, as does an information board indicating what would be grown where, with lots of detail in the Fife and Tayside areas.

This community garden is open to the public year round and “illustrates the close relationships between science, agriculture, land use and the environment”.

As the garden is supplemented with lots of information boards, it allows visitors to learn and understand the areas and habitats presented in the garden.

More information can be found at Living Field website and blog (there is also lots of good information on the original website, now mothballed).

Balruddery Farm

by Kaska Hempel

It was a bitterly cold afternoon, with wind cutting through our coats and gloves. But the view over the experimental fields at Balruddery Farm, together with the stories from our guide, Geoff Squire, gave us a bit of a warm and fuzzy feeling.

We have all heard that modern agriculture can be an extractive industry – damaging soils, biodiversity, increasing risk of flooding and causing pollution. Before us was a living proof that these effects can be reduced and even reversed in a typical Scottish rotational arable cropping system, and it could be done without significant losses to economic profitability.

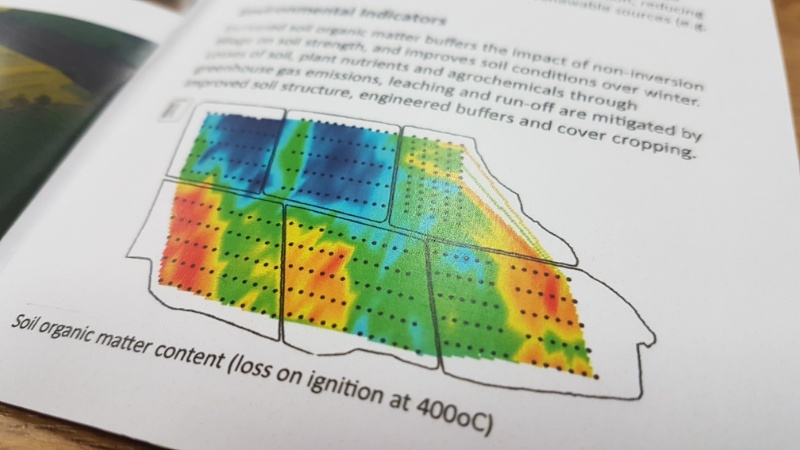

We heard all about it earlier in the day, straight from Dr Cathy Hawes, an ecologist involved in the research. The experiment focuses on 6 common Scottish crops (winter wheat, potato, spring barley, spring beans, winter barley, winter oil seed rape). The first full crop rotation of six years has now been completed, yielding interesting results indeed! So far, the sustainable cropping regime methods are showing better performance on the multitude of environmental and ecological indicators. But most impressively, the new regime does not seem to compromise economic viability so far (with an exception of winter wheat). News that should warm the cockles of any farmer’s heart.

But what most impressed me, was that this approach can also help us fight climate change. More organic matter in the soil means more carbon captured and stored away from the atmosphere. Emissions of nitrous oxides and methane, usual for standard farming methods, can also be lowered. It has been recognised that, in theory, taking care of the soil could contribute immensely to achieving the much needed zero carbon emissions. Here is an experiment which provides the precious hard data in support of this theory.

It was also a pleasure to see the wildlife seemed to be thriving here too. Goldfinches and other small birds taking advantage of the interconnected hedgrow habitat, a herd of deer browsing in the wild field edges, and a busy buzzard soaring above us. A little pond at the back of the farm sheds, full of rushes looked like a perfect hideway for frogs. There were also bat-boxes affixed to the shed facades. It was clear that in this working farm landscape, a lot of care was taken to give space and home to all sorts of creatures great and small.

I will definitely be up for another visit in the spring or the summer, for a walk among the fields, and the Balruddery Den down below.

You can find out all about the project on their website. There are also a lot of information boards scattered about the farm, which is open to the public.

Cool crops: Beans and Peas

by Andrea Roach

In Scotland we are famous for growing a few things. Cereals, mainly for whisky production. And potatoes are grown because they are in high demand and easy to cook with. Unfortunately, they reek havoc on our soils and are at huge risk to an increasing number of pathogens in our changing climate. Yet, we import a huge amount of beans and pulses.

Dr Pete Iannetta and his research team at James Hutton is looking to see what else we can grow domestically. And like his coffee mug reads: “I heart’s Beans”, well, he loves beans.

Why beans are so good? Yes, they are delicious, healthy and packed with protein and carbohydrate. What makes them more exceptional than other crops is their ability to improve the quality of soils in food production as beans and other legumes add nitrogen to the soil. You can grow them without having to add fertilizers that can cause problems to the water run off. What I found interesting was that by intercropping beans with wheat, more nitrogen is additionally fed to the beans by the wheat and vice versa. Both the wheat and the beans produce a better yield for growing together; it is not a one way street here thanks to the working in the soils.

The team are also looking closely at the waste product of beans for animal feed to reduce imports and their potential for more sustainable drinks such as a pea gin or bean beer. Pea gin, for instance is carbon neutral as supposed to a wheat gin that has a carbon cost of 2.3kg of CO2 per 70 ml bottle.